The Serbian elections in March of 2014 were the tenth legislative elections and the seventh election since the introduction of a multiparty system in 1990. The results reveal the dynamics of both the electoral landscape and of the political parties in Serbia. A very active campaign and a turnout of 53.09% notwithstanding, even when combined all of the (self-) proclaimed social democratic parties that ran in the election did not manage to get more than 30% of the vote.

It is particularly troubling that the majority of votes were for three supposedly different social democratic electoral registers – that of the Socialist Party of Serbia (SPS), the Democratic Party (DS) and the New Democratic Party (NDS). If we take into account the Social Democratic Party of Serbia (SDPS), which formed part of the governing coalition with Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic’s Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), there are in reality four social democratic electoral registers. Nevertheless, though the inescapable ‘moral force’ of the moderate Serbian Left normally forms an electoral coalition with the pro-liberal and anti-nationalist Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), the latter did not manage to win any seats in the National Assembly. That five purportedly social democratic parties advanced competing electoral lists appears paradoxical to a Western observer. We will elaborate on why this “Serbian paradox” is not one later on.

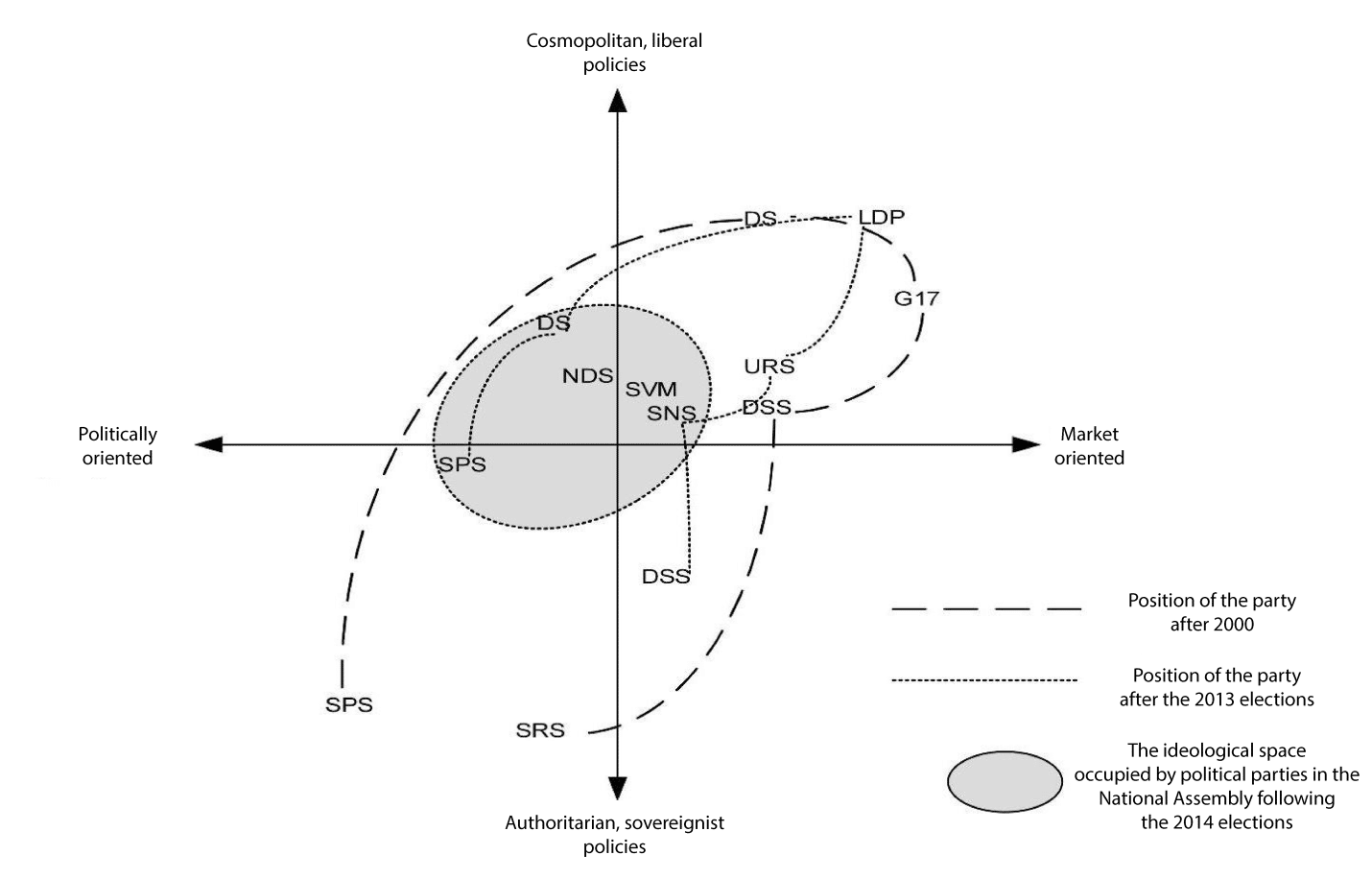

By way of an introduction, it is important to highlight that the last legislative election in Serbia considerably remodeled the political landscape of the country – see graphic 1 for a comprehensive illustration of the recent changes (1) – when compared to the 2000s.

The principle result of these elections is the shrinking support for both the Eurosceptic and pro-European parties (2) as neither of their representatives managed to surpass the 5% electoral threshold.

In other words, 2014 was marked by a clear victory for the Eurocentre, also known as the Eurorealists. The “electoral earthquake” of 2014 led to a complete collapse of the so-called “pro-democracy” organisations that caused the fall of Slobodan Milosevic’s government in 2000 after a decade long struggle. Likewise, the reformed nationalist leaders and their parties (for example, the SNS which counts among its members the President and the Prime Minister), previously pillars of Milosevic’s regime, enjoyed a triumphant return that received the full support of the international community this time around.

Following more than a decade in power under Tadic, the former victors lost their legitimacy given the deterioration of the Serbian economy, corruption and their incompetence in the face of the 2012 crisis. They did; however, learn their lesson: they marched towards power, donned the European mantle and used anticorruption rhetoric as the easiest means of toppling the established political elite. The question arises: which group represents the majority of Serbian society? The half of the electoral body that abstained from voting does. In a parliamentary democracy, such a high level of abstention in legislative elections clearly demonstrates the non-representativeness of the political system as a whole. We will endeavour to paint a social and economic picture of the post-socialist transition that engendered the current political crisis.

Two Decades of Post-Communist Transition in Serbia: The Example of a Devastated Country

The constitutional changes of 1989 and the adoption of a new Constitution in September 1990 officially put an end to the one party system founded on the dominance of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (the official name used by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia from 1952 onwards) and restored competition between political parties within a parliamentary democracy that initially dated back to the pre-communist Yugoslav monarchy. Although the Serbian government inherited (from 2006 onwards) a republican structure from the communist era, the “real socialism” (as a social framework) and the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (as a political framework) belonged to the past. Acting in its own self-interest, the new political and clientelist capitalism not only denounced “real socialism” and international socialist identities in their entirety, but also genuine democracies. The imposition of constrained ethnic identities and symbolic divisions was an enabling factor in the plundering of public and social assets from communist Yugoslavia. In reality, war was but one means through which a “fertile terrain,” necessary for the transfer of numerous privileges from a single-party to a multi-party system, was created.

The destruction of the economy and of society was largely interest driven. Sociological studies have shown that two thirds of the largest private sector entrepreneurs that appeared over the course of the 1990s were from among the former communist nomenklatura. This number ranged from one quarter to one third in other post-communist countries (4). The so-called Yugoslav Left, that is to say individuals who used and abused this term, largely contributed to this process. This serves as a warning of the dangers represented by the different intellectual fetishisms, constructed without analysing the contents of daily terminology, surrounding the implicit “angelic purity” of the political left. In fact, the aforementioned concepts of a multiparty system and of democracy were founded on an authoritarian pluralism underlying the hegemony of a single party. As the dominant party during the 1990s, Milosevic’s Socialist Party of Serbia (SPS) adopted this approach and attained a scary degree of control over the population. At the same time he secured and controlled his own political and economic interests, as well as those of his inner circle. His hysterical nationalism and xenophobia ignited and ultimately caused him to lose the Balkan “micro-imperial” wars. The destructive manœuvres of this political organisation, characterized by “economic pillaging,” resulted in a 60% drop in the GDP compared to the period preceding the dissolution of socialist Yugoslavia. They thus created a social situation in which; for example, industrial production only represented 43% of its 1990 level ten years after the beginning of the transition to capitalism. Like Ukraine, Serbia beat the record for the largest annual drop in GDP with a decline of 59.4% in 1992. Furthermore, the dominant reforms of the 1990s led to a reduction in workers’ rights, a highly fragmented society and a reversal in the social and civil gains made in the after-war period more generally. Consequently, capitalist countries such as Sweden and France, to mention but a few, embody socialist paradises in comparison to Milosevic’s “socialist” Serbia (5). The result of these policies is felt in the social structure of the Serbian population at the turn of the century: 40% are below the poverty line, 40% are on the verge of poverty, 15% belong to the middle class, 4.95% to the upper class and 0.5% are extremely wealthy.

Taken all together the defeats during the Croatian and Bosnian wars, the sanctions, the demonization of the country in international public opinion, the enmeshing of the country with organized crime, the pretense of parliament, the massive impoverishment of all social strata and the new war launched in Kosovo, dealt a lethal blow to the Milosevic regime. Under pressure from an increasingly unsatisfied population, the opposition unified and partially rid themselves of nationalist folly and isolationism (7). Even the nouveaux riches no longer had any reasons to support the regime despite the practically unlimited privileges it had given them. They had already adapted their privileged positions, as inheritors of “real socialism,” to capitalism. Nevertheless, in order to continue enriching themselves and to establish their social and economic influence, they needed political and economic stability which the former government could no longer offer them. This explains the change in sides of a large part of the “lumpenbourgeoisie” (Karel Kosik) – for example those who suffered under the embargo – as well as their direct support for the Democratic Opposition of Serbia (DOS), which had associated themselves with the Democratic Party (DS) just before and immediately after the “Bulldozer Revolution” of 5 October 2000.

The ten years between 1990 and 2000 were defined by economic destruction, pauperization and the large-scale polarisation of society that generated radical changes within the regime. They were equally defined by the transition from a phase of criminal political capitalism to that of corrupt political capitalism (8). This peripheral authoritarian capitalism, Max Weber’s “political capitalism,” distinguishes itself by the fact that the economic success of a person is directly related to their proximity to power. Consequently, political connections are essential for any professional career.

As of yet unfinished, this second phase of political capitalism is characterized by a country’s departure from autarky and isolationism, as well as by their integration into political and economic international organisations. When the DS was in power, the new liberal orthodoxy of neo-conservatism led to the arbitrary replacement of communist irrationalities with new ones, resulting from a blind fealty to the neoliberal dogmas of market fundamentalism and their peremptory application on all levels of society. This was reflected in the downplaying or outright rejection of all contemporary progressive social trends and experiences that were going on in developed, less developed or developing societies. The unreserved acceptance of neoliberal ideology and the post-socialist strategy of transition were quite simply presented as the “express road towards a Western and European society of abundance” for the small post-communist, then post-Milosevic, peripheral state.

Inherent within neo-liberalism is the idea that “workers are lazy and capitalists are good,” which guaranteed that the new regime socially and ideologically supported the moneyed class of the 1990s as they were considered the new avant-garde called upon to drag society towards better days. In this context workers were regarded with suspicion, they were considered the leftovers of socialism and self-government, behind which hid a culture of disorder, strikes, inferiority, laziness and other malaises. Furthermore, the role of the country during the post-socialist transition was limited to defending the interests of the dominant classes in Serbia and internationally, who ultimately only further ravaged the Serbian economy through a corrupt process of privatisations.

In this way, the ruination of the economy, politics and society represents a strategy of legitimisation of the “Milosovian” political and criminal capitalism at the heart of a process led by the DS since 2000. Although these last two decades may well have been different, they are founded on the same economic philosophy of production, and reproduction, of a system of economic oligarchy, the subordination of all segments of society for the profit of a minority and the annihilation of the real economy.

The Absence of Social Democracy: The Characteristics of the Serbian “Social Democratic” Parties

To understand the political context dominating Serbia since the fall of “real socialism,” it is important to understand the characteristics of Serbian political parties in general, and more specifically those of the social democratic parties.

In reality, there are no political parties that meet the literal definition of the term, be it in Serbia or in other post-communist countries. Indeed political parties represent social classes and specific portions of society, whereas countries such as Serbia, that are in transition towards a semi-colonial form of capitalism and who’s viability depends exclusively on the size of investments and loans from the West, have no solid social base. On this point, parties evolving in countries with weak and fragmented unions, with corrupt media and an atomised society were disappointed by the vested interests of their leaders and their members (9), but also by the considerable Serbian and international capital involved as well as the continuous contradictory demands from the United States, the European Union and Russia. It could be concluded that the major Serbian parties have a tendency of adopting a technocratic and managerial structure, a role as a “comprador” (10) and that their social and economic programs and policies are identical.

Even though the single party communist system was eliminated in 1990, the mono-ideological context that reinstates and anchors the most powerful political actors has still not been eliminated. The major part of those working within the League of Communists of Yugoslavia during the period of “real socialism” were never able to, nor did they ever desire to, call into question their political club or the privileges they enjoyed.

Today this is replaced by a shallow form of parliamentary democracy that, due to the bias of the parties in the government and the media services controlled by the nouveaux riches, stifle all expressions of independent politics. The Yugoslavian League of Communists and its factions have only been replaced by new political factions. Therefore it is not rare to be faced with a cacophony and coalitions that would quite simply be inconceivable in more developed democracies. Indicative of as much, the current government is constituted of a coalition regrouping parties espousing liberal, conservative, social democratic and radical leftist ideals.

Despite the general reduction of the importance of the political positions of parties in practice (a process that is particularly visible within the European social democratic parties, who’s ideological profiles have always been more clearly represented than in the other political groups), Serbia has achieved its own post-ideological consensus. The Left-Right divide plays absolutely no role in political life. Moreover, the manifestos and the platforms of parties, which are “social democratic” in name only, have no concrete influence over their actions. Their political action and their internal functioning still rest on the absence of democracy and on the concept of a “grand leader.”

There are currently six social democratic parties in Serbia that regularly participate in elections: the Socialist Party of Serbia (SPS), the Democratic Party of Serbia (DS), the New Democratic Party (NDS), the Social Democratic Party of Serbia (SDPS), the League of Social Democrats of Vojvodina (LSV) and the Social Democratic Union (SDU). It is also worth mentioning the Movement of Socialists (PS), the party of the current Minister of Labour Aleksandar Vulin, that has a social democratic orientation but declares that they are from the “radical Left” – a fact that does not prevent them from appearing on the electoral registers of the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), the equivalent of the UMP in France.

Despite its small size, the SDU played a relatively important role within the opposition to Milosevic during the nationalist hysteria of the 1990s. Nevertheless, as they are not represented in Parliament and have been deprived of all influence over Serbian society, and given that the NDS – who became the Social Democratic Party (SDS) during their first congress on 4 October, 2014 – was just recently formed from a section of the DS who remained loyal to the former President Boris Tadic and who are still situating themselves politically and ideologically (11), that the LSV is a regional party and that the SDPS of the former Labour Minister has never participated independently in the elections (12), we will concentrate on the two most important supposedly social democratic parties: the Socialist Party of Serbia (SPS) and the Democratic Party of Serbia (DS).

The SPS is the legal inheritor of the League of Communists of Serbia. It originated from within the most retrograde nationalist branch (that of the former leader Slobodan Milosevic), that he took up again after the ideological struggle in the second half of the 1980s. Milosevic abruptly became the first president of the party, formed the 27 July 1990. In power until the legislative elections of 2000, it was also the most influential political party.

Due to their policies during the 1990s, this fake Left was never accepted within Socialist International or other leftist organisations, clearly illustrating how they never had any legitimacy with the international Left during this period. Given the socio-economic situation described hereinabove, it goes without saying that that the nationalist policies of this party were first and foremost responsible for the destruction of Yugoslavia as a Republic of Southern Slavs, but also in all likelihood, the long term prospects of the movement and the idea of Yugoslavism – something that had a lasting impact on the history of the Balkan Left. Political assassinations, electoral fraud, hawkish and isolationist policies, an extreme fragmentation of society and the destitution of the people, a drastic rollback in labour laws and the creation of a class of nouveaux riches that form an integral part of the oligarchic policies of “the Left,” are but just some of the lasting “successes” of the PS, cradled as they were in the bosom of the “savage capitalism” (Helmut Schmidt) that had taken hold in Serbia.

However, after the SPS’s experience during the 1990s and the arrest of several political leaders for corruption and war crimes (some of whom, Slobodan Milosevic included, were judged in front of the International Criminal Court in The Hague), Ivica Dacic initiated a veritable turnaround from 2008 onwards. During this period, the party began discreetly distancing itself from its communist past (from 1945 to 1990) and its bellicose policies (from 1990 to 2000), and entered into the “pro-democratic” camp by joining with the Democratic Party.

From 2008 to today, the SPS have endeavoured to legitimize their modern social democratic identity in terms of their doctrine and on the international level. According to their website, and statements made by official representatives, their next stated objective is to join the Progressive Alliance. In power since 2008 and at the head of the government from 2012 to 2014, the SPS was accepted as a legitimate partner by EU representatives and the party has confirmed that one of its principal objectives is the adhesion of Serbia to the EU. Given the timid statements made by the party leaders during their last congress on December 14 2014, it is possible to observe a distinct distancing from their policies of the 1990s. That being said, the SPS and the other political parties constitute, for the most part, merely a “federation of interest groups and lobbies.” Furthermore, their so-called social democratic political platform does not prevent them from participating in governments with liberal and conservative parties, nor does it stop them approving a law that set labour laws back several centuries, making it equivalent to England in the 19th century and abrogating some of the few remaining modern benefits.

The second self-styled social democratic party is the DS. As opposed to the SPS who inherited the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, the Democratic Party was founded by diverse dissidents during the era of “real socialism” who’s only real commonalities were their opposition to communism and their pro-Western stance. This internal ideological cacophony undermined the confidence of the party members in the leaders. The latter went on to form new parties, ranging from the liberal Left to the decidedly conservative (the DS generated more than five major political parties in this way). During the 1990s, the DS was one of the major opposing forces to the SPS’s regime. Nevertheless, they were rejected by the national/conservative European political groups due to their nationalism at the time. Immediately following the changes in 2000 and the destitution of the SPS, Zoran Djindjic, Prime Minister and the President of the Democratic Party at the time, launched a top-down process of “social democratisation” and a rapprochement with the European socialist parties.

Thus, the DS was born as a centrist force and is today a full member of Socialist International and a member of the Party of European Socialists. But according to several sociological studies, Serbian citizens and party sympathizers do not see the Democratic Party as such. The position of the former president of the DS, Boris Tadic, elected 27 June 2004, elaborated during an interview, is revealing: despite the current path taken by the party, he identifies as liberal and not a social democrat, or even from the Left more generally (13).

Since 2000, there has been a short term improvement in the quality of life of the middle classes in Serbia. Moreover, the country also placed better internationally with more political freedom, a relative stability and a partial democratisation, thus marking the post-communist transition that finalised the process of privatising social capital that was lead by the privileged few close to the party oligarchs. The party does; however, have several distinguished young intellectuals with social democratic leanings. It also enjoys a strengthened position due to their adhesion to Socialist International. Nonetheless, the party has only very few points of convergence, ideologically and in terms of internal organisation, with European social democratic parties and even then only with those furthest on the Right – all while claiming to represent the “new centre.” The release of the recent platform was marred by scandal: the absence of the term “social democratic” – described by the president of the DS as an oversight that would be quickly rectified. But the terms “socialism” and “social democracy” were already missing from the last program, meaning that any individual having read it would never have guessed that the DS is part of Socialist International.

According to several studies, centrist members and the electors of the party only considered social democracy, or the Left more generally, with amazement or at best indifference, until recently. While the newly elected president of the DS, Bojan Pajtic, announced a social democratic pivot, it is not yet possible to draw any conclusions from the party’s new alignment. The Democratic Party could be a potential social democratic actor in the future, though it is still too soon to tell – even if they join the PES.

European Policies and Serbian Social Democracy: What to do?

As could be expected, Serbian politics have very little ideological structure. In the words of the sociologist and social democrat Srecko Mihailovic, ideological debates are absent from parties or marginalised in favour of the struggle for power. Moreover, power is not even taken into account in this context as it is but a means to get a part of the economic spoils (14). The liberal economist Vladimir Gligorov therefore states, rightly so, that the structure and the internal organisation of a party is but a framework for interest groups. Indeed, internal debates dealing with ideological or strategic questions are few and far between. Everyone is focused on climbing the ladder of the party hierarchy as ascending it gives access to power and positions in sectors where the party is influential (15).

It is therefore not surprising to see that the largest political group in Serbian society is that of those who abstain, which in turn poses a serious legitimacy crisis for the Serbian parliamentary democracy. Nevertheless, a majority of the voters do not vote according to political platforms or other criteria, but instead vote for those who they perceive to be the least corrupt, or simply more capable of standing up to the runaway corruption that is undermining society.

In conclusion, the political situation rests on the two following foundations or consensuses and concerns all major Serbian political parties:

1. the mantra of the EU is used as an excuse to justify backward policies that destroy citizens’ social rights;

2. the technocratic management of the country serves the interests of national and foreign capitalists and is set against the backdrop of the inextricable links between politicians and the Serbian nouveaux riches.

The supposedly social democratic political parties do not have a sustainable strategy and have no real chance of progressing within the current political and ideological quagmire. It may well have to wait until the arrival of a new generation of political men and women, trained at the Friedrich-Ebert Foundation, present in Serbia for more than ten years. In any case, the “pro-European” policies of these parties and their intention to join the Party of European Socialists (PES), represents a prospective future as it would permit the formation of a fixed group that could complete their “social democratisation.” Without the aid or the pressure from the PES, it would be difficult to initiate such a change in Serbian social democratic parties. In such a context it is important to turn towards the Socialist Party of Serbia and the Democratic Party, as they possess the most potential, and broach the following points:

1. the formation of an official commission within the PES by people who know the lay of the land in Serbia and who would therefore be qualified to evaluate the current situation of these parties, followed by the creation of a strategy adapted to deepen their “social democratisation;”

2. support the creation of a social democratic think-tank as a platform that would help the social democratic parties locate their ideas and strategies on the Serbian political spectrum. The long-term objective of the institute would be to reconcile the different Serbian social democratic parties so that they can share strategic advice and coordinate politically.

3. support training initiatives and the work of task forces within both of the aforementioned parties in order to elaborate more solid policies founded on social democratic ideology and the specific platform of each party;

4. promote an extensive training program on social democracy for party leaders and members;

5. and support the process of internal democratisation in these parties by drawing on the experience of other European social democratic parties.

In order to commit to these positive changes, it is obviously necessary to revitalize unions and civil society in general, because without pressure from unions and workers, all political parties, no matter how leftist they may be, are condemned to bow before capital and implement the corresponding right wing policies.

Notes

1 – The graphic is taken from de Zoran Stojiljkovic and Dusan Spasojevic, “Partijski sistem Srbije: dug put od polarizovanog pluralizma ka segmentiranom pluralizmu” (The Party System in Serbia: The Long Road from a Polarised Pluralism to a Segmented Pluralism), in Zoran Stojiljkovic (dir.), Politička sociologija savremenog društva (Political Sociology of Contemporary Society), Institute of Textbook Publishing, Belgrade, 2014, p. 489.

2 – It deals with political parties working towards accepting without reserve the entirety of the economic and social conditions, but also those related to Kosovo and those concerning NATO membership (needless to say, a very delicate point for a country that endured 78 days of bombardment by the Alliance during 1999 because of the fighting in Kosovo) set by the EU in Serbia, and accompanied by a simultaneous distancing from Russia.

3 – The most Eurosceptic and extreme right wing party, the Radical Serbian Party, received 2% of votes during the last elections whereas they regularly won between 20 and 30% these last decades. In contrast, the pro-European parties, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and the United Regions of Serbia (URS/G17+), did not manage to get into the Serbian National Assembly. Together they did manage to win more than 10% of votes during the last election, however.

4 – Malden Lazic, Promene i otpori (Changes and Resistance), Filip Visnjic, Belgrade, 2005, p. 94.

5 – Some Western authors have even baptised Serbia under Milosevic as the “last bastion of communism” and socialist countries due to the name of his party: the Socialist Party of Serbia.

6 – Danilo Mrksic, “Restratifikacija i promene materijalnog standarda” (Restratification and Changes in the Material Standard) in Mladen Lazic (dir.), Račji hod. Srbija u transformacijskim procesima (The March of the Crab. Serbia in the Process of Transformation). Filip Visnjic. Belgrade, 2000, p. 17.

7 – During the 1990s, even opposition parties advanced nationalist rhetoric. The Democratic Party (DS), today a member of Socialist International, is often seen as the most progressive fraction of the “anti-Milosovian” coalition members at that time. They clearly addressed the issue of national order as of the first multiparty elections, whereas their deputies sitting in the National Assembly publically demanded “the Western definition of the Serbian State.” Zoran Djindjic, then president of the DS, even received applause from the socialists when he commented that “relinquishing the autonomy of the Croatian Serbs was not a synonym of peace, but of capitulation.” The party’s leaders then accused Milosevic of having been vanquished during the war, albeit without sanctioning participation in it. The idea being that they wanted to present themselves as being more valiant than the Serbian ex-leader.

8 – We have addressed this subject in another publication: Ivica Mladenovic, “Basic features of the transition from nominal socialism to political capitalism: the case of Serbia”, Debatte, vol. 22, n° 1, 2014, p. 5-25.

9 – Serbia is but one of the post-socialist countries and is evolving within a partitocracy just like the others. Indeed, the political parties are increasingly present. If they want to remain in power on the local and national levels, given the current generalized socio-economic crisis in which unemployment rates are over 30%, they need to bribe the poor by distributing jobs within the public administration to their members. The party currently in power, the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), has more than 330,000 members according to their most recent data. In the eyes of a Western observer, this could be seen as incredible. It is worth remembering that Serbia has a population of less than 8 million people and more than 90 registered political parties. Serbian citizens are simply very aware of the fact that their only chance if accessing a job is through a political party.

10 – Michael Ehrke, the former director of the German social democratic Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Foundation in Belgrade, has largely addressed the role of the elite compradors in post-socialist countries in his writings. Michael Ehrke, “Oligarsi, kompradori, tajkuni : tri tipa dobitnika” (Oligarchs, Compradors, Magnates: The Three Winners of the Transition), in Srecko Mihajlovic (dir.), Dometi tranzicije od socializma ka kapitalizmu (The Fallout of the Transition from Socialism to Capitalism), Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, CSSD, CeSID, Belgrade, 2011, p. 151-163.

11 – The undemocratic internal organisation of these parties means that any personal divide or any issue linked to the interests of the leaders of the Serbian political leaders (without delving into political or ideological divides as no major differences exist between the parties any more) often ends with the issue being dropped by the “weaker camp” in the conflict and the creation of new political parties.

12 – This political group is the paradigm of the pre-political situation that the Serbian democracy currently finds itself in. In effect, during the 2012 legislative elections, the SDPS formed a pre-electoral coalition with the Democratic Party, the most influential political party and in power at the time. But after the elections and the unexpected defeat of their coalition, they accepted the invitation of the new right wing victors, leaving their previous alliance and joining the government in power until the elections in 2014. In those elections, the SDPS joined a coalition formed around the largest Serbian right wing party, the Serbian Progressive Party, with whom they form a part of the majority government currently in power. At the end of the day, the president of the SDPS has been permanently in power since 2000 be it within government on the “right” or the “left.”

13 – See also: <http://news.beograd.com/srpski/clanci_i_misljenja/stankovic/001111_Potrebni_su_nam_politicari_po_nasoj_meri.html>.

14 – Srecko Mihailović, “Identiteti političkih stranaka i njihovih programa, dvadeset godina posle” (The Identities of the Political Parties and their Programs, Twenty Years Later), in Slavisa Orlovic (dir.), Partije i izbori u Srbiji (Partis et élections en Serbie), Belgrade, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung and the Centre for Democracy at the Faculty of Political Sciences, 2011, p. 190.

15 – Vladimir Gligorov, “Programi i politike” (Political Platforms and Politics), in Zoran Lutovac (dir.), Ideologija i političke stranke u Srbiji (Ideology and Political Parties in Serbia), Belgrade, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 2007, p. 224.